The Legacy of a Too-Often Forgotten Houston Designer Lives on in This Stunning Private Home

Inside One of the Pioneering Sally Walsh's Last Surviving Interiors

BY Catherine D. AnsponThe Grand Hall looking east. Casa Bella Gabriella Crespi brass swing-out table. (Photo by Pär Bengtsson)

Sally Walsh blew through every stereotype of her time.

She was Hans Knoll’s number two in Knoll’s Chicago office; a partner and a peer in eminent Houston design, furnishings and architecture firms Evans-Walsh, Wilson, and S.I. Morris Associates; celebrated nationally with extensive press in shelter and trade magazines; and tapped for the plum commission of the era: Braniff Airlines HQ in Dallas, the $75 million corporate playground unveiled in 1978 that was as lavish and innovative as the Apple or Google campuses are today.

Along with that project, she designed a swank pad at DFW Airport for the original power couple: Braniff CEO Harding Lawrence and his wife, advertising pioneer Mary Wells Lawrence.

Flash forward four decades. Braniff is long gone, and Sally Walsh — who was inducted into Interior Design’s Hall of Fame in 1986 for her work forging a modern aesthetic in Houston — has largely been forgotten outside a knowing niche within the city’s architectural community.

Twenty-eight years ago, she passed away from a rare blood cancer at the age of 65. With the exception of a generously endowed annual lecture in her name sponsored by the AIA, there’s been waning memory and little physical evidence of Walsh’s contributions, which were transformative to the world of interiors in the era that saw Houston’s rise as a great American city: the late 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s.

At that time, the zeitgeist was that good design could change lives, impacting the workers and work done in law firms, banks and industry that defined a burgeoning post-war metropolis.

Improbably there was no greater designer for the new city than a woman raised in the deserts of the American Mexican border and South Dakota, who received schooling under the tutelage of “the fifth God — Hans Knoll,” as Walsh would cite on her resume.

Into that Houston, which was about to become Space City, Walsh strode in 1955, a confident, svelte, quick-witted and stylish figure with a penchant for Balenciaga and Christian Dior, a charismatic woman newly married to a man who would become a top Texas lawyer, William Frederic Walsh, who became partner in Percy Foreman’s firm.

Walsh exercised design control over 100-plus major projects encompassing boardrooms, trading floors, lobbies, Lear jets, and C suites. All the while her eye was on the common man and what Good Design For Everyone, as she called it, could bring.

While the commissions and often the corporations for which they were created are no longer extant, the cult of Walsh lives on. She’s being rediscovered for her big ideas about modern design, sense of classicism and proportion, and ability to create interiors in a new design language, working with signature elements from her toolbox — Knoll furniture was always paramount, as well as custom fabrications from her go-to Houston source, Brochsteins.

Seeing Walsh’s Greatness

It’s difficult to gain a sense of Walsh’s genius, as her signature projects have not survived or are no longer in their original form: the interiors for the Houston Public Library Jesse H. Jones Building and the Kinkaid School Library, M.D. Anderson Hospital (before Cancer Center was part of its name) and Methodist Hospital, the University of Houston Student Center and Rice’s Student Memorial Center, the Schlumberger headquarters and Gulf Oil Chemicals, and every bank of significance within the region were all the designer’s calling cards.

However, one of two fully intact Walsh interiors is still in existence — and it’s a rare residential commission that the designer created for a couple who were close friends, Susan and Raymond Brochstein (whose name graces Rice’s civically minded Brochstein Pavilion).

After four decades, the modestly private couple has opened their home and its Sally Walsh-designed interiors for PaperCity. Our feature fortuitously coincides with renewed interest in the designer’s work: the creation of the public philanthropic opportunity of the Sally Walsh Endowed Professorship and Student Scholarships at the University of Houston Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture and Design, and the upcoming publication of a definite volume on Walsh, being written by Alan Bruton.

In the beginning was the house. It took a triad of architects to bring it to fruition in 1974 — the Rice mafia. Raymond Brochstein was the original architect; he and his wife, Susan, had owned the forested acre in West Houston (now close-in Memorial) before they could afford to design a home.

She sensibly persuaded him to keep the land until that day came, and it did. When struggling with the final design, Brochstein enlisted two Rice professors, William T. Cannady and his own mentor, Anderson Todd.

Within a week, they had the final working plan. Susan recalls Raymond coming home and saying, “They put us in a shoebox, and it works.” The stark white stucco home — Todd mixed marble dust into the final coat of stucco, and there’s been no need to paint it since — in its sylvan setting was referred to as the Tree House.

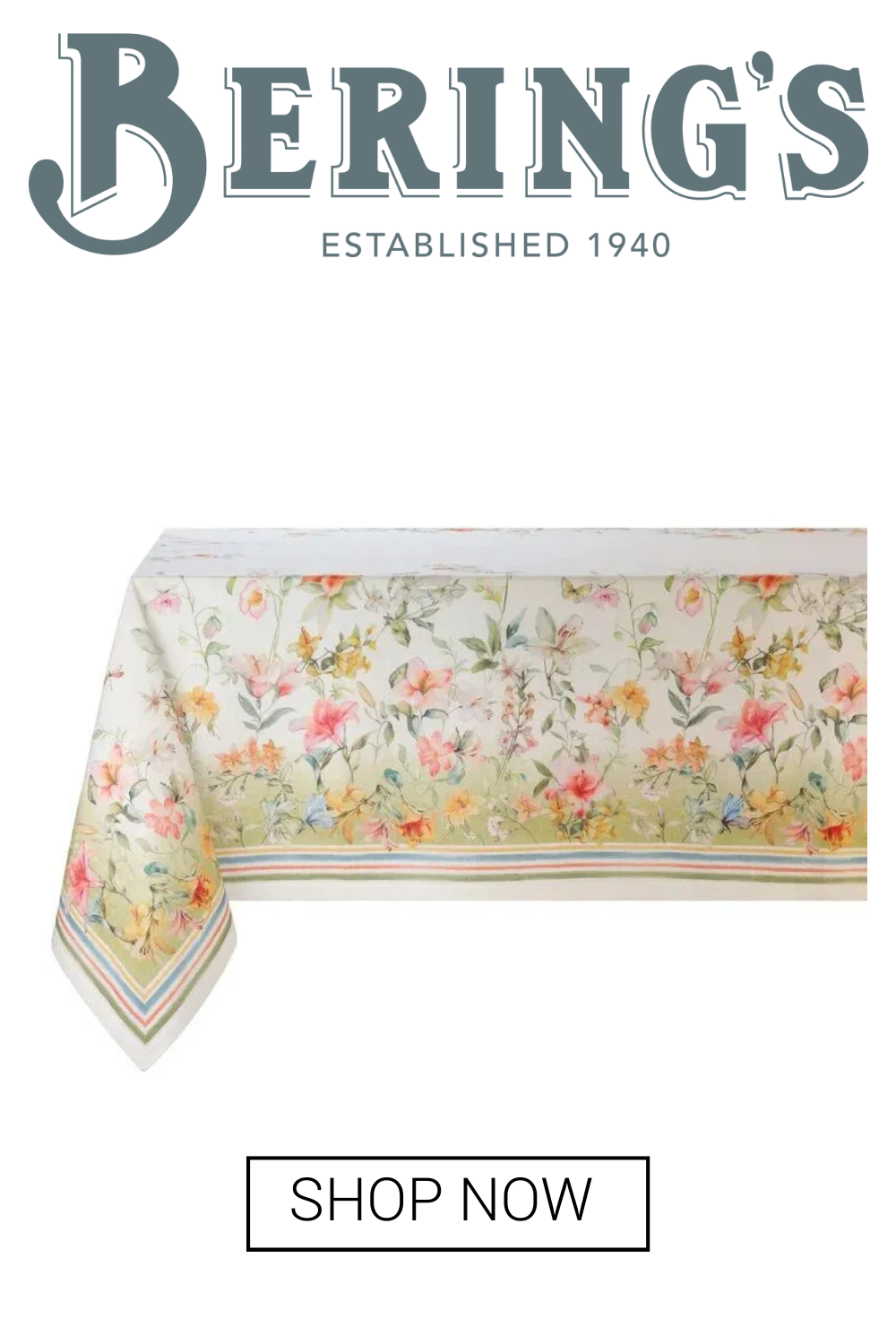

Its 75-foot long, two-story Grand Hall, informed by a bank of windows lining its back deck bring the deciduous trees, set upon a shallow ravine, into the field of vision of anyone who sits in the first-floor living space.

The Brochstein House went on to win the Texas Architecture Honor Award in 1975 and was published the following year in Texas Architect, the regional magazine for the AIA. Decades later, it received the AIA’s 25-year award in 1999.

The Brochstein Story

The Brochsteins, who recently celebrated 60 years of marriage, raised their family here. Susan Brochstein, who grew up in Mississippi and was Tulane-educated, was the daughter of a rabbi who railed against segregation and his polymath wife, whose intellectual curiosity would rub off on her daughter.

Raymond Brochstein, FAIA, is a first-generation American and scion of the 85-year-old Brochsteins; now retired (daughter Deborah Brochstein and son-in-law Steven Hecht are at the helm now), he took Brochsteins from a regional firm for fine woodworking to one where he routinely received calls from architects such as Richard Meier — and ended up crafting interiors for the architect’s billion-dollar Getty Museum.

It was Alan Bruton, professor and director of interior architecture at UH, who introduced us to the Brochsteins and thus, the Brochstein House. Bruton’s book on Sally Walsh, which is in the research phase, is filled with the recollections of the Brochsteins, who were among Walsh’s closest friends, as well as many other collaborators, clients, colleagues, friends, and the family of Walsh.

Raymond describes Walsh as an “incredible, brilliant person” who arrived like a thunderbolt. It was 1972.

“I met Sally through Magruder Wingfield, who was also a partner in S. I. Morris’ firm,” he says. “Sally was the first female partner there — hired to lead its interior architecture department. She designed the first Transco Offices that Hines built, before Transco Tower, with an open plan — the cabinets were all built by Haworth I think, and they were sagging.

“Mac said to her, ‘Why don’t you go out to Brochsteins and see what they can do.’ Mac called me and arranged an appointment for Sally. So we pulled the cabinets apart and put the levelers on the panels. And it worked. And I could do no wrong after that. Anyway, that’s how we got to know each other. From then on, whatever she wanted to do — we did.”

Walsh became part of their multi-generational family of makers, along with her greatest partner in crime, Raymond, the tenacious CEO, whom she called Bear.

He was her problem solver, and later she would claim she learned everything about furniture from him. They worked on epic jobs together, museum-caliber works of decorative art.

“I hate to tell you, but we haven’t moved anything since she died,” says Susan of Walsh’s unerring placement and pitch-perfect take on furnishings, objects, nature and art.

“This has been here all this time.” She points to a furniture grouping, then to the dining-room area and its dynamic painting by L.A. talent Chuck Arnoldi.

“There’s one problem with the house,” she says. “It’s too comfortable.”

Light dances and dapples throughout the Brochstein House, changing with times of day and seasons.

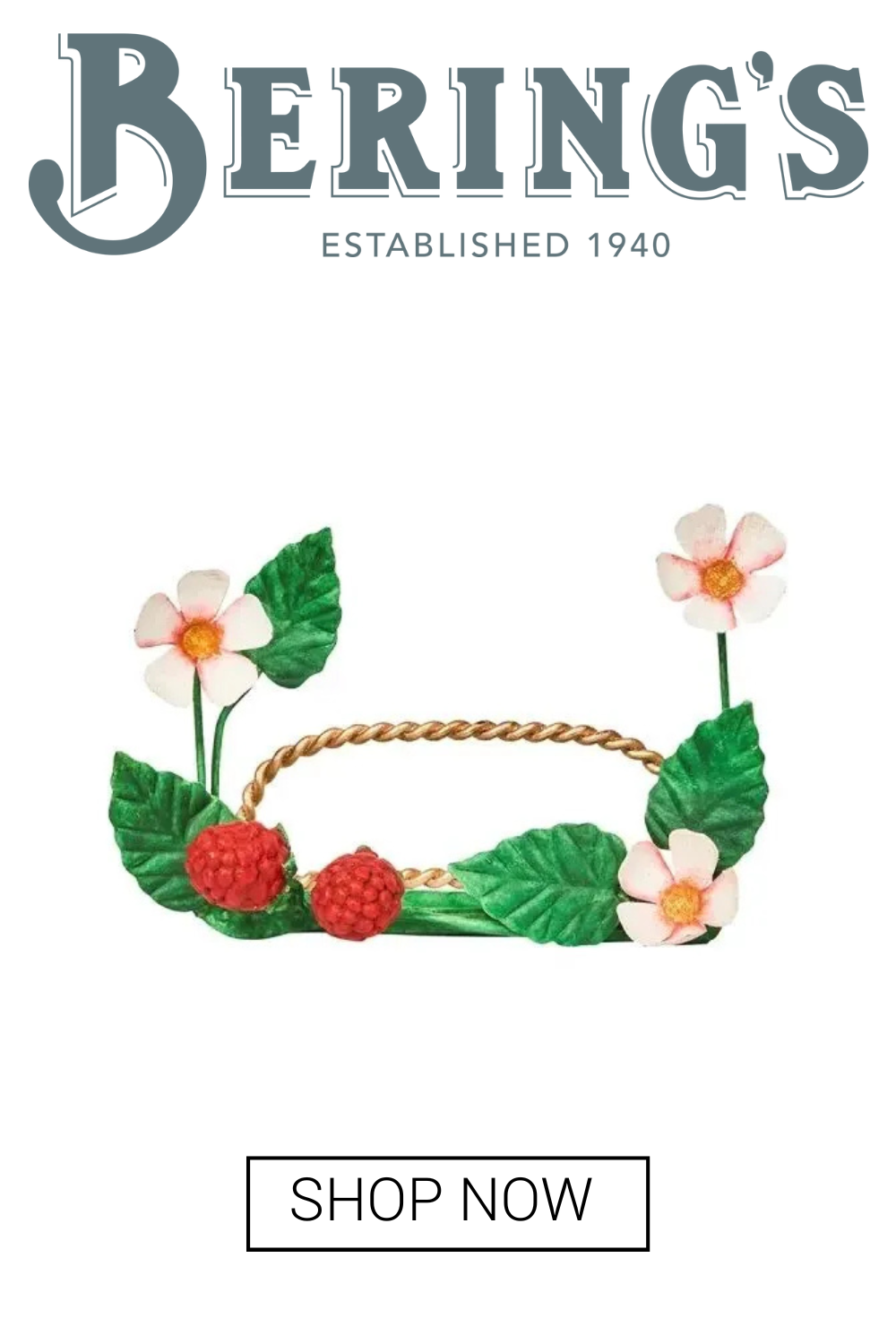

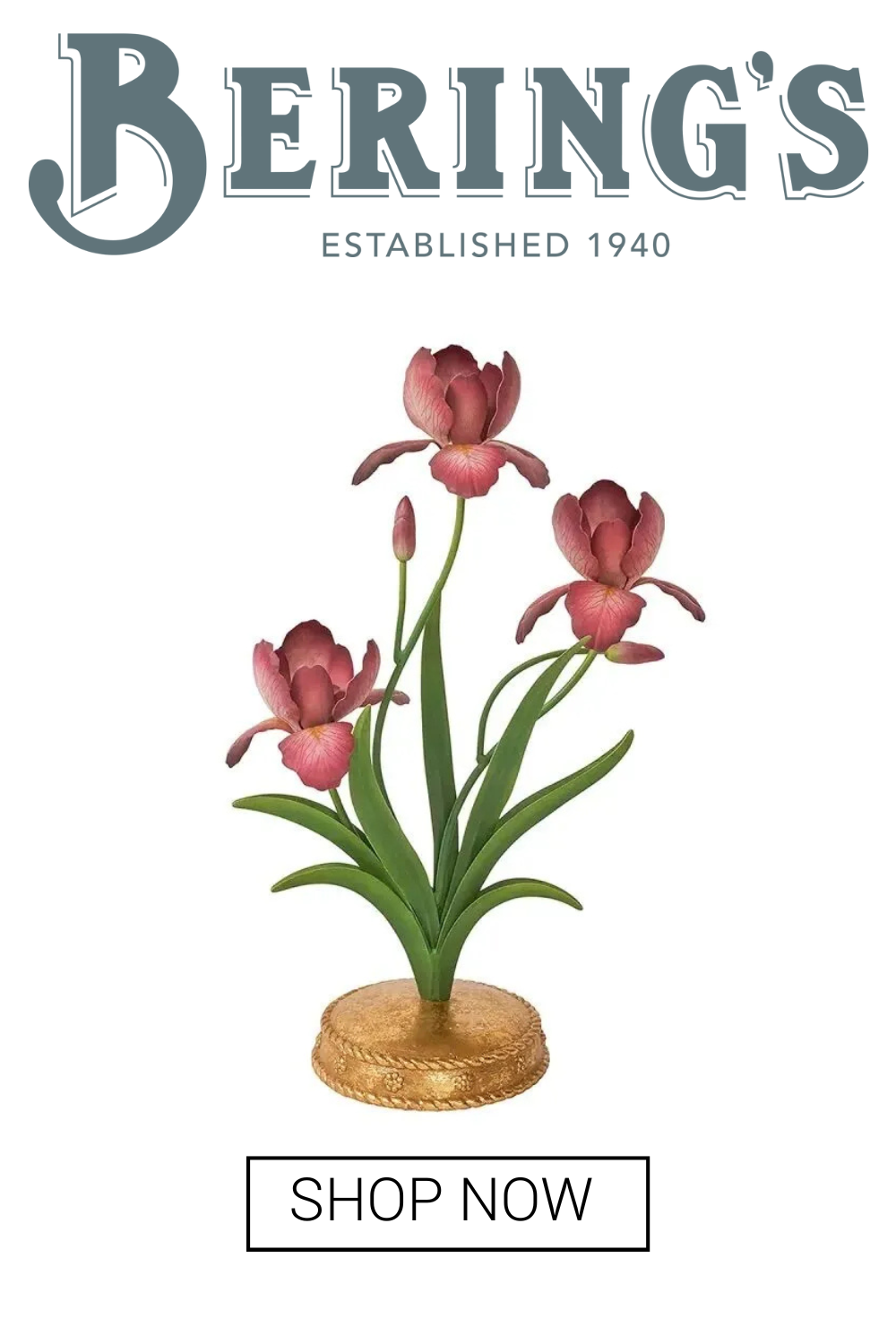

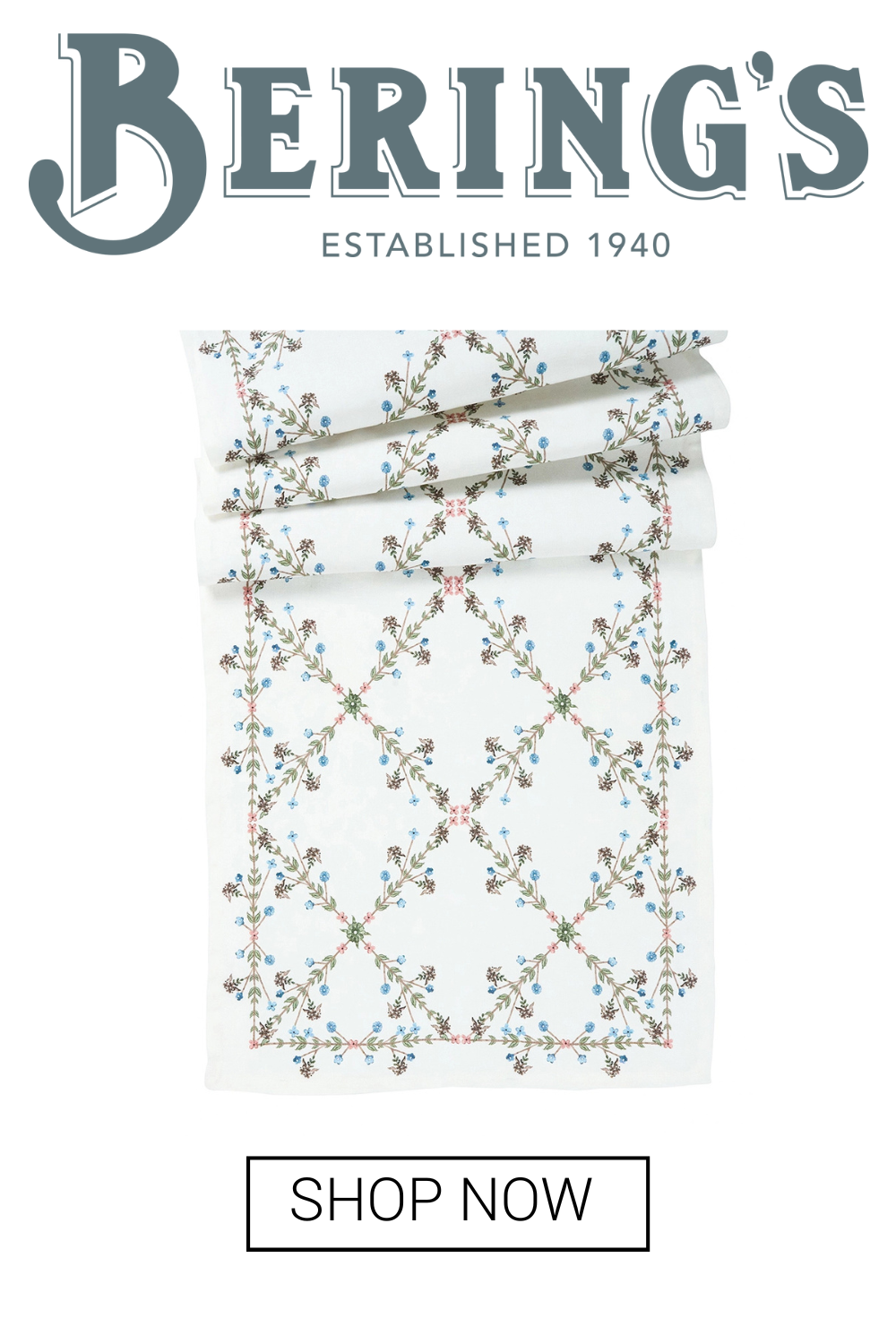

Its Grand Hall still soothes and delights: the plush, jewel-tone J L Larsen carpets on the stairs and library; the Woody Gwyn canvas of palm trees from Meredith Long & Company that anchors the west wall; the aggressively robust, hand-hewn Chuck Arnoldi painting that Walsh positioned down to the half-inch over the dining room table; and the industrial capstan entry table; down to the Gabriella Crespi for Casa Bella brass table, and three molds in the living room used to make women’s hats that would be at home in The Menil Collection’s Surrealism galleries — are evidence of Walsh’s fearless ability to discover beauty in the everyday, and she and Raymond’s shared value in the making of things and the tools of their making.

Morning turns to afternoon, and Susan says, “She was a character. She never had children, but she mothered the world.”

Bruton adds, “Walsh chose not to focus on a practice in the domestic interior, though she could do it so beautifully. She worked precisely so that her design had the maximum impact on the maximum number of people. She believed in the public interior, understanding that high quality design affects people’s lives in a way that can change things. She’s inspirational to the next generation of true design progressives.”

“Raymond Brochstein realized this when he raised the support for the annual Sally Walsh Lecture in the 2000s, and now it’s becoming time to get the word out to a new generation about the positive impact a Sally Walsh Endowed Professorship and Student Scholarships can have on Houston through design.”

Raymond states that Walsh brought modern design to the city of Houston — and to the country.

Like an F. Scott Fitzgerald novel, a note of Wynton Marsalis jazz, or a Matisse cut-out, Walsh’s interiors subtlety appears effortless. It’s the result of an eye, decisions, elements, and confidence.

With her higher-profile commissions long gone, the DNA of Walsh, her vivid personality, and unique creativity live on most fully here, within the Brochstein House.