Celebrate Iconic Fashion Photographer Richard Avedon at His Blockbuster Exhibition at the Amon Carter

In Conversation With Laura Wilson, A Dallas Photographer Who Assisted the Late, Great Artist

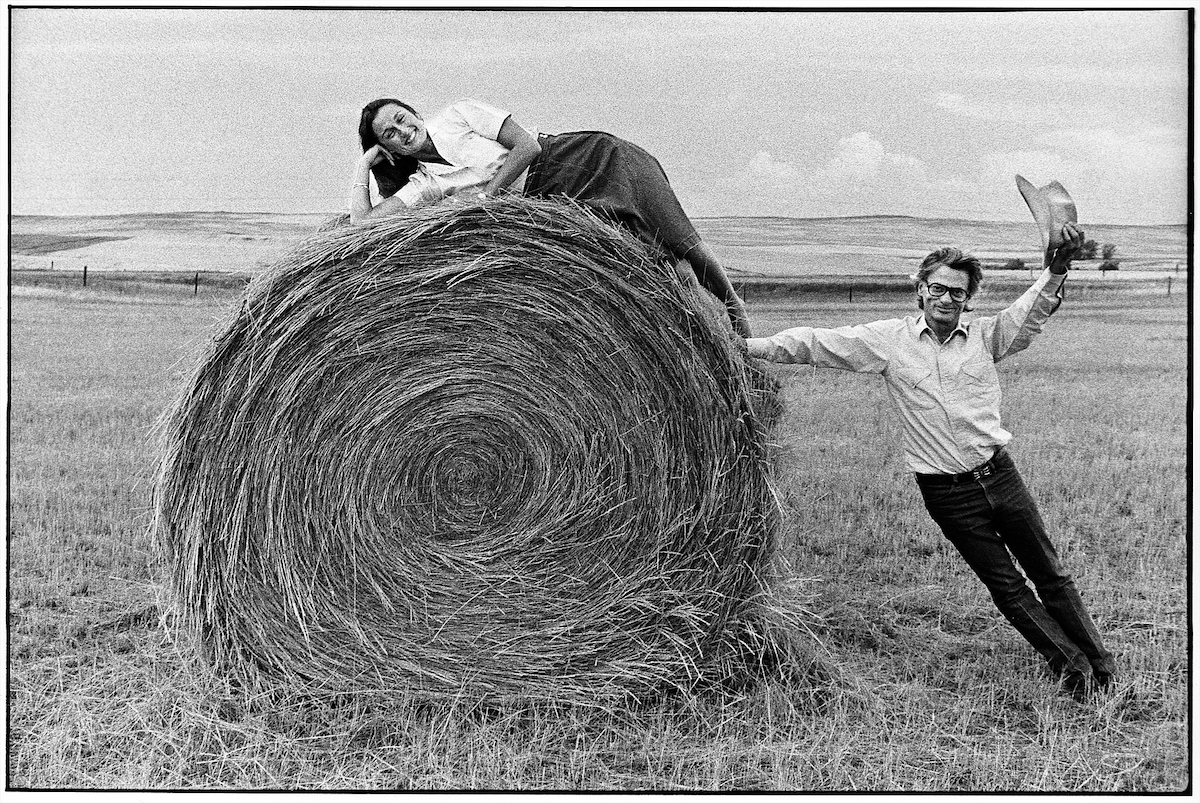

BY Catherine D. Anspon // 09.18.23Richard Avedon’s Ruby Mercer, publicist, Frontier Days, Cheyenne, Wyoming, 7/31/82 (AMON CARTER MUSEUM OF AMERICAN ART, FORT WORTH; © THE RICHARD AVEDON FOUNDATION)

On the occasion of the 100th birthday of Richard Avedon and his blockbuster exhibition of searing portraits of the West at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Catherine D. Anspon chats with Dallas photographer Laura Wilson, who assisted the great Avedon over the course of six summers, from 1979 through 1984, organizing 752 sittings that exposed 17,000 sheets of film and orchestrating photo sessions in 189 towns throughout the swath of the Great American West, often with young sons Owen, Luke, and Andrew Wilson along for the ride.

The now iconic “In the American West” series is acknowledged as a milestone in American photography and the art of portraiture, commissioned more than 40 years ago by the Amon Carter. The photographs are a bellwether in the history of the photographic medium, as is Wilson’s own volume, Avedon at Work: In the American West, which celebrates its 20th anniversary. Wilson reflects upon Avedon the artist, the subjects who shattered the myth of the West, why these portraits stand the test of time, and how this assignment shaped her own path as an artist.

Catherine Anspon: Let’s begin with how you were introduced to Avedon. I know it was through your late husband, Robert A. Wilson, whose advertising and graphic design firm worked with the Amon Carter Museum.

Laura Wilson: It was quite a wonderful experience to be a young photographer who had admired Richard Avedon my entire life. He dominated photography, fashion photography, beginning in the ’40s and into the ’50s, and certainly the ’60s and ‘70s. So, I was very excited about the possibility of meeting him. We went to New York — Mitch Wilder, the director of the Amon Carter, and my husband Bob — to talk to him about doing a project of portraits of people in the West. He said, “Absolutely, yes.” At that point in his life, after working for 40 years in fashion photography, he was looking for a new creative inspiration.

CA: Where was the initial meeting? LW: We went to his apartment on the Upper East Side, which was above his studio, up a flight of stairs. It was small, compact, but very interesting, very appealing. And we had lunch with him. He was very engaging.

Both my husband and Mitch Wilder liked him very much. Within a month or two of this meeting, Dick flew to Fort Worth. He came to our house. We had three young boys [Luke, Owen, and Andrew Wilson], and he was very interested in our family life. That’s when I had a sense of who he was. We went to the Amon Carter, where he saw the museum itself and the exhibition space, and then we had dinner with Mitch Wilder, who was a very unusual museum director in that he was entrepreneurial as well as visually very sophisticated.

CA: Letter of a lifetime.

LW: Dick said, “I think I’m going to need somebody who will be able to guide me in the West.” He wasn’t going to say, “I don’t really know anything about the West” — which, of course, he didn’t, because he had spent his entire working life in New York. He was very embedded in the New York intellectual life, in theater and in literary circles. It was a very stimulating, culturally rich life.

I don’t know if there is another photographer now who has the same kind of impact and fame that Richard Avedon had at that time. Even Irving Penn, who was a brilliant photographer and very much admired, didn’t have the same fame that Dick had. In any case, I wrote him a letter and said that I would very much like to work for him, and I would do anything that he needed done. I agonized over my letter. When he got it, he picked up the phone and called me immediately and said, “Let’s do a weekend together in Sweetwater, Texas, for the Rattlesnake Roundup.”

He wasn’t going to commit; he wanted to work with me and see how it went. After the first day at the Sweetwater Rattlesnake Roundup in March 1979, he said, “I want you to work on this project.” I was taken aback that he didn’t spend more time considering this. He made a good choice, though, because I worked very hard for him.

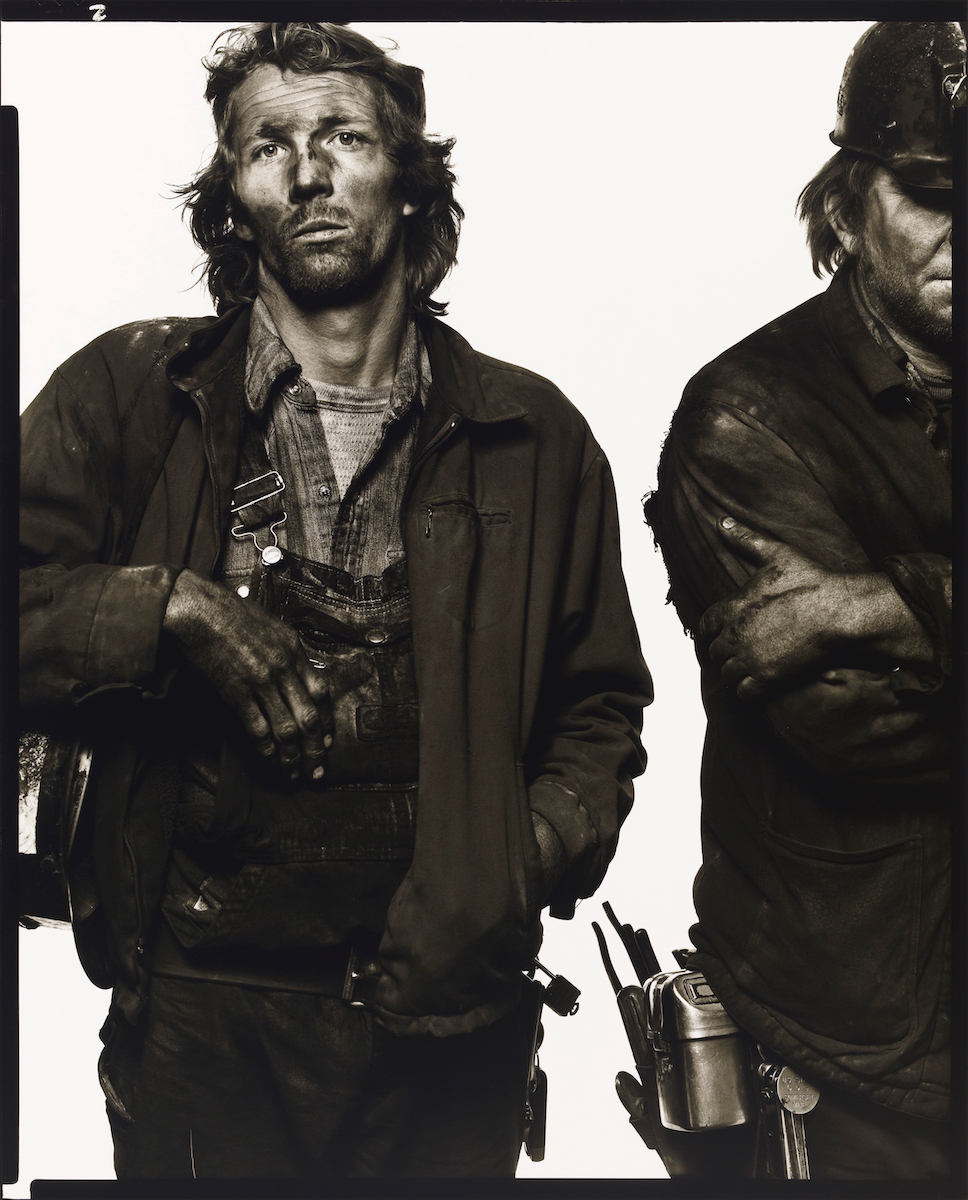

CA: How did you gain access to difficult subjects, such as the miners in Colorado?

LW: That mine in Colorado was closed to the public in the sense that outsiders wouldn’t have been welcome there. But I was on a plane coming from maybe Montana back to Texas, and I sat next to a man who, after he realized what I was working on, said “You know, if you’re interested in coal mining, there’s a man who is Mr. Coal in all of Colorado.” He gave me the name and telephone number. When I called him, he was willing to allow us access. And once we got where we needed to be, we were a very appealing group. Dick was strange looking to these people at first. He was short in stature, had kinetic energy, and was a New Yorker, but once they got to know him a bit—it would be within 20 minutes or so — they always opened up. He was brilliant at dealing with all kinds of people.

CA: The idea of a museum commissioning an entire body of work …

LW: It was very unusual. It had never been done before — a photographic project commissioned in advance of seeing the photographs. It was a five-year project.

CA: Mitch Wilder sounds like somebody who didn’t need to see things beforehand. He understood the artist’s vision. Did he and the Amon Carter look at the work along the way?

LW: Mitch Wilder died early in the project. He saw only the first work. A new director was hired, and he and the head of the board were not admirers of the work. But they committed to this five-year project, and to their great credit, they kept the commitment. So now we have this amazing body of work. And when you see it now, it’s as strong if not stronger than it was when I first saw it in August of 1979. It’s an incredible body of work. I was just in New York and saw the portraits at the Gagosian Gallery. It’s incredible what Dick did, and how much foresight he had.

CA: Were you involved in choosing the subjects of the 752 photographs?

LW: I don’t know if you’ve been on the set of a movie, but everything is a pyramid, and everything leads to the top of the pyramid. And that’s the director. Every good director has an assistant director, and that’s what I was … I did choose some of the subjects. One time, we had gone to a coal mine. I saw a miner going underground in the morning, and I thought, ‘Gosh, he’s got an amazing face. He’s great. He’s perfect.’ So, I spoke to him. “When you finish your shift, may we photograph you?” He nodded. Eight hours later, when the shift was over — we wanted to photograph him covered in the day’s work — the miners came up in a rush to shower and then left. I had told Dick about him. But I didn’t see him. I went to the foreman and told him who I was looking for, and he said, “Oh, he didn’t want to be photographed, so he slipped out.”

I was very disappointed. I went back to Dallas for a few days, and Dick stayed two or three days longer. He went to a Mormon church on Sunday, and he was looking around at the congregation. That was his reason for going; I won’t say it was so much a spiritual reason. The miner I had wanted to photograph was there, but Dick didn’t know that. As church ended, Dick went up to him and said, “You know, I would really like to photograph you.” He said, “I can’t believe it. I tried to get away from the woman who was with you.” So that’s how in sync we were. That was in Utah. The man is in the book. He has a wonderful face. He’s standing with his two sons on either side of them.

It was very lucky for both of us that I had a very good eye. It just happened that my personality and my vision synced with Dick’s.

CA: These are photos that have kismet, a serendipity.

LW: But it was very planned. I spent the year preparing for shoots. I mapped out every day because we had no time to waste. Dick was supporting a big studio in New York, and he was at the height of his career. Every month, he had the cover of Vogue, Vanity Fair, GQ, and other major magazines. He wasn’t lackadaisical. There was no sense of ‘Well, if it works, fine. If it doesn’t work, that’s fine.’ No, it had to work.

CA: There was a lot to process and plan.

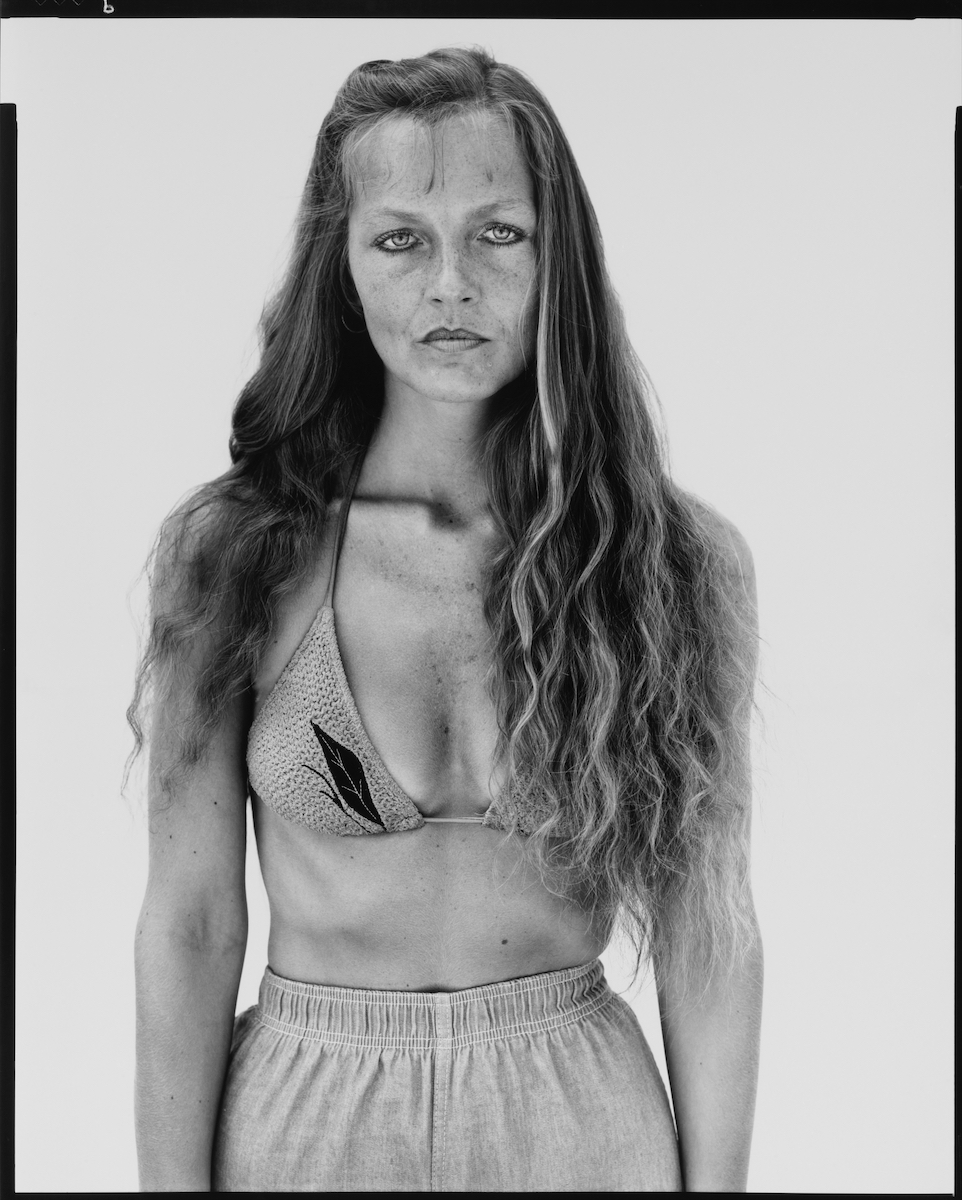

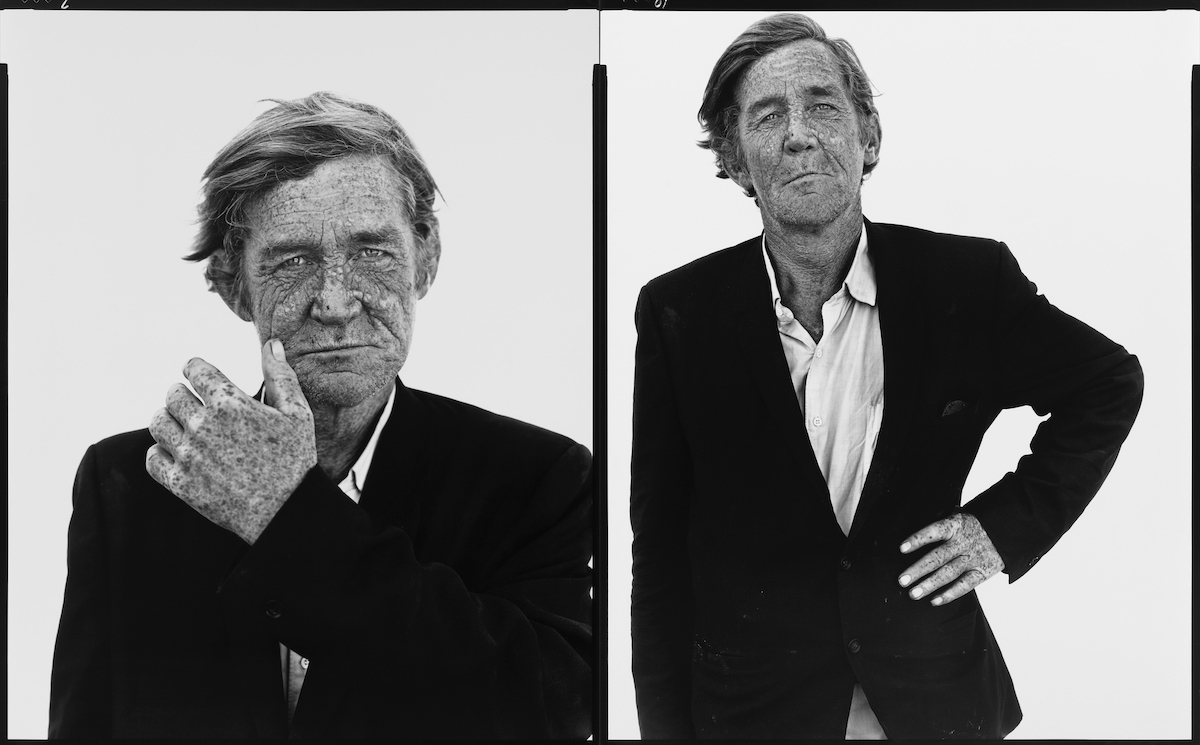

LW: Dick was commissioned for five years, but the project extended into the sixth year. It was a fantastic education for me. Could you imagine anything better if you were someone like me, obsessed with the American West and with photography in equal measure. So, to work with the world’s most famous photographer, and to be in an area where I had historical knowledge but no real contemporary knowledge — I didn’t know about uranium mines. I didn’t know about slaughterhouses … I was learning things that were critical to what Dick wanted. He wanted to photograph the West now. He didn’t want a romantic extension of a John Ford movie.

CA: You actually kept diaries. And you photographed along the way.

LW: That was something Dick said from the beginning: “Take pictures and keep a diary. When I do this book, I want you to write the text.” He kept the pressure on. There was no mañana in his way of operating. He had worked all his life under deadlines. You know what that’s like. Dick wanted me to be a part of it in a very substantive way — by keeping a diary, by recording it photographically, by making choices of who should be photographed, and speaking to everyone. I was the one who went up to a subject — because it’s much easier for a woman to go up to another woman, or man, and say, “That photographer, standing over there with the big camera, wants to take your picture” — and explain who he was and what he was doing.

CA: Were the subjects intimidated in any way?

LW: What’s interesting is that people sense the importance of being photographed by that camera. It’s a big camera, the Deardorff. And it’s on a tripod, and there’s white seamless background behind, with the photographer, me, and two assistants. It wasn’t just a snapshot. And it wasn’t a quick newspaper photograph. As important and memorable as snapshots are, this was something different. And people might have felt a little self-conscious, but when they got in front of the camera, the dignity and the vulnerability within the person came through.

One time I said to a coal miner in Paonia, Colorado — this was five, six years later, when I called to ask him if he’d gotten a copy of the book and if he’d like to come to the exhibition — “Do you remember us?” And he said, “Yes, I do.” Then I said, “What do you remember about being photographed?” He said, “My father died in the mine. My uncle died in the mine. And my brother died in the mine. And I knew he was trying to get that out of me.” I mean, that’s amazing. To be able to articulate that six years later. And in such a poetic way. That was the great gift of being exposed to hard-working people.

CA: Over 40 years later, what is your reaction to the images from the Amon Carter show, “Avedon’s West”?

LW: I’ve seen it twice in one month. Each of these times, they’ve just knocked me out. I think they are incredible. They’re so strong and so moving, emotionally powerful. I am in awe of what he accomplished.

CA: Maybe that’s why the series hasn’t always been shown. Because of the humanity — it’s not the myth of the West.

LW: That’s right. It’s not the myth of the West. The myth of the West was John Wayne, John Ford, and Gary Cooper; but this is the West.

CA: Did you and Richard Avedon stay in touch?

LW: Yes. We stayed in contact throughout his life. I was with him when he died in San Antonio in 2004. He asked me to work for him on what became his final project, which he was shooting for The New Yorker, photographing people involved in democracy in America. His subjects were activists, political leaders, people who were victims of political positions, burn victims being shipped back from the war in Iraq and Afghanistan. He died from a stroke. The morning of the day he died, we were to photograph a woman at 12:30 pm. He was disoriented and confused. I said, “We have to go to the doctor.” He said, “No, I don’t want to go. We’ll go to the doctor after I do this.” Then he had a brain aneurysm. That last project was published posthumously in The New Yorkerhttps://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1958/11/08/a-woman-entering-a-taxi-in-the-rain.

CA: What’s next?

LW: I’m working on a project for the Meadows Museum in Dallas on Mexico. Opening February 2025. It’s 30 years of photographs taken in Mexico, all in large-format color. And The Writers photographs are going to Chicago. They’ll be shown in October at Lake Forest College. Then in 2025, they’re going to the Houston Public Library Downtown. That will be a big show — 150 photographs.

“Avedon’s West,” at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art, Fort Worth, through October 1, cartermuseum.org.