Houston Artist El Franco Lee II Turns His Love Of DJ Screw, JR Richard and Other Unique Characters Into Enthralling Paintings

Playing With Pop Culture and the Human Figure

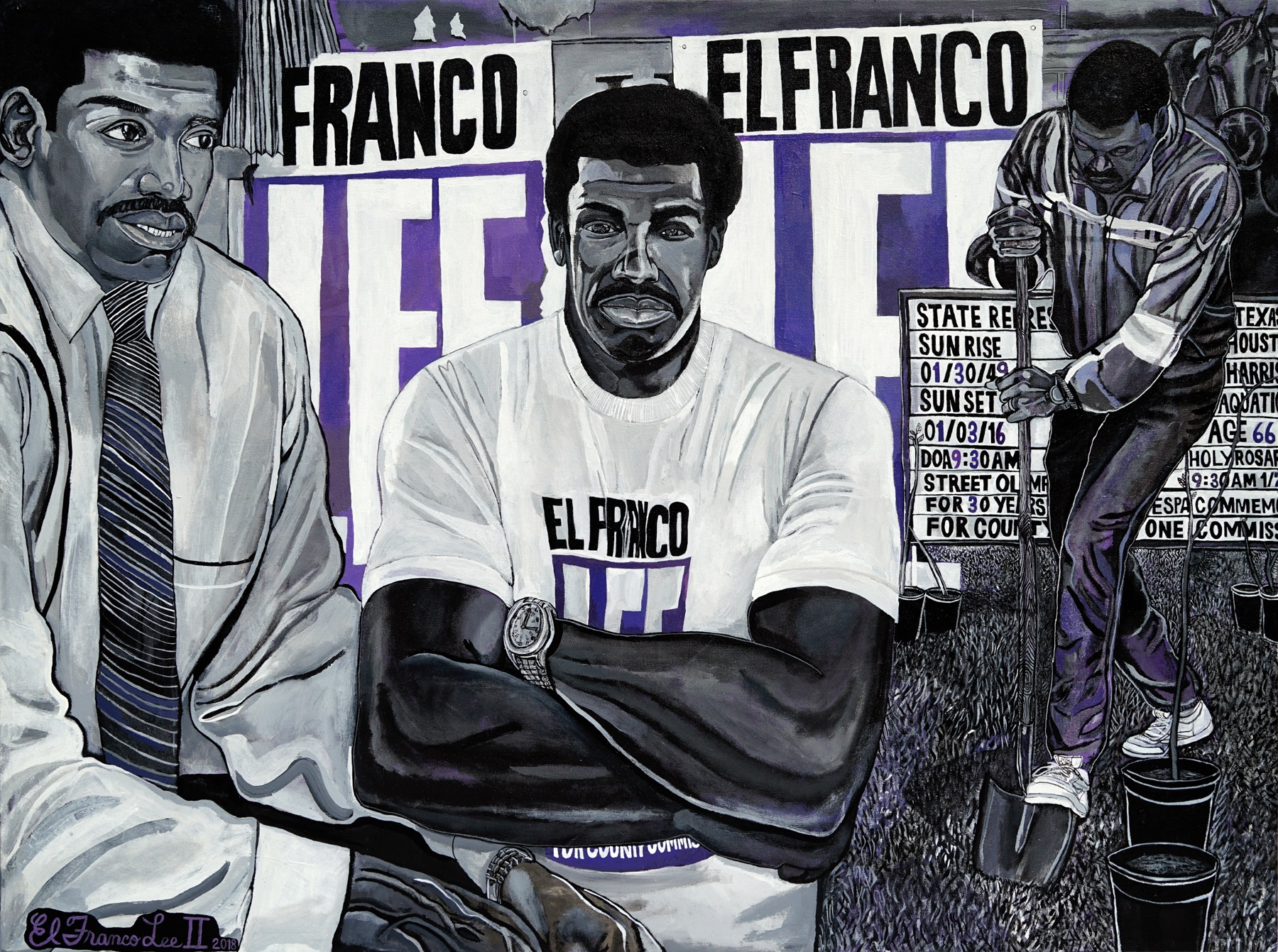

BY Ericka Schiche // 09.01.23El Franco Lee, father of artist El Franco Lee II, was an important community political figure in Houston for many years. Lee served as a Texas State Representative from 1979 to 1985, and as Precinct 1 Harris County Commissioner from 1985 to 2016, when he passed away. (Courtesy Estate of El Franco Lee).

Channeling the dystopian zeitgeist in all its complexities is certainly an everyday working reality for artist El Franco Lee II, a native Houstonian and DJ Screw aficionado from Houston’s Fifth Ward.

From dramatic post facto scenes to striking tableaux vivants, Lee’s paintings expose viewers to realities news cameras seldom capture. Significantly, Lee’s Houston-centric focus enables him to tell stories — albeit in a painterly way — that are both enthralling and informative. Often revealing the dark, grotesque side of humankind, no theme or subject is off limits for Lee. These days, he is a breakout star who is rising in the art world on a national and international scale.

Coinciding with the 50th Anniversary of Hip Hop, the Baltimore Museum of Art recently mounted a sold out exhibit dubbed “The Culture: Hip Hop and Contemporary Art in the 21st Century.” Lee’s painting, DJ Screw in Heaven (2008), is featured prominently in the exhibit. Currently on view at the St. Louis Art Museum, the exhibit will then travel to Schirn Kunsthalle in Frankfurt, Germany through May 2024 and the Art Gallery of Ontario, Canada through March 2025. Lee’s work also traveled nationwide as part of the Valerie Cassel Oliver-curated “The Dirty South” exhibition. And here in Houston, his Christopher Blay-curated “Mid-Career Survey” casts a spotlight on 20 years of Lee’s art-making at the Houston Museum of African American Culture. That show runs through this Saturday, September 2.

Placing an inimitable artist like Lee and his work in art historical contexts is a challenge since he travels solo, creating his own trajectory and unique genre. But looking at Romanticist painter Francisco de Goya’s grotesque Saturn Devouring His Son (ca. 1819-1823) from the Black Paintings series, it is easy to tangentially connect Lee to the Goya continuum. Unlike the Goya-obsessed Chapman Brothers, however, Lee considers himself more of an aesthetic heir to The Sugar Shack (1976) painter Ernie Barnes. As a child, he would stare at The Sugar Shack during the opening credits of Good Times, as Blinky Williams sings the words “Keepin’ your head above water!”

“Every time someone would ask who my influence was — in undergrad, grad school, studio visits — I’d tell them Ernie Barnes,” says Lee, who also teaches painting at the University of Houston-Downtown.

Both Lee and Barnes also played football. Lee played running back and outside linebacker on the St. Pius X High School varsity team in Houston. He developed an interest in architecture after years of working in his father’s architectural engineering firm ESPA Corp. But after pursuing architecture professionally and academically, he later switched to visual arts. Lee eventually received his Master of Fine Arts degree from the University of Houston in 2013.

And Barnes — who passed away in 2009 and was nicknamed Big Rembrandt — ended his National Football League career with the Denver Broncos.

In addition to Barnes, Lee cites Jean-Michel Basquiat, Frank Frazetta and Spawn creator Todd McFarlane as artists who have inspired him.

Throughout his career, he has created drawings, sculptures, montages and paintings. Working in a style he refers to as Urban Mannerist Pop Art, Lee connects the term urban to his deep interest in hip hop.

“Pop Culture is what is going to connect the viewer to the work,” Lee says. “In some cases, there’s going to be components that strike a nerve with the viewer and make them want to connect to what this painting is about. If it’s just one little nostalgic detail that derives from somebody’s upbringing or past. . . it kind of draws them into the imagery.

“The mannerist approach to painting would be the final part. I mainly keep all of my work about a figurative dialogue. Everything is about the human figure and the way you can tell a story by guiding the viewer’s eyes across the composition with the human figure.”

In addition to the short list of artists who have inspired Lee, perhaps the most profound influence in Lee’s life is that of his own family. His father, the late Harris County Precinct One commissioner El Franco Lee, broke barriers as one of the most powerful politicians in Texas. And his uncle Bob Lee worked alongside Fred Hampton in the Chicago-based Illinois chapter of the Black Panther Party.

According to Lee, his uncle was “Fred Hampton’s field general, right hand man. Whenever he spoke, he was with him. He was supposed to be with him during the time of the assassination.”

Lee and Hampton also founded the original Rainbow Coalition in Chicago on April 4, 1969. The younger Lee says his father and uncle both wholeheartedly supported his artistic career.

Although Bob Lee passed away in 2017, his collages, along with paintings of El Franco Lee II, were included in the younger Lee’s show entitled “Lee’s Congo Barre” (2019 to 2020) at Fifth Ward art space Mystic Lyon. The “Barre” in the exhibit title references syrup drinking culture, which Lee says began in Fifth Ward. He cites this show as one of his all-time favorite exhibits. Fifth Ward has been home to the Lee family for decades.

His grandmother Selma Lee owned a nightclub in the neighborhood called Lee’s Congo Bar, which was the namesake for Lee’s exhibit.

“She was one of the few women entrepreneurs over here amongst a lot of activity and businesses on Lyons Avenue,” Lee notes. “She also had a boarding house behind Lee’s Congo Bar. It was a two-story boarding house, a small apartment complex where offshoremen would stay when they were in town.

“People that were performing in the nightclub, like B.B. King — anybody on the blues, Chitlin Circuit she was connected with — would stay there. She was really good friends with B.B. King. He would come quite often.”

Lee also speaks fondly of the Gray family, longtime friends his uncle Bob introduced to the Lee family. Mike Gray, Academy Award-nominated co-screenwriter of The China Syndrome (1979) and producer of American Revolution 2 (1969), was a Lee family friend from the late ’60s until his untimely death in 2013. Gray met Bob Lee while in Chicago. The two struck up a lifelong friendship.

For many years, his son Lucas Gray worked as an animator for The Simpsons. He later directed the controversial “Mortyplicity” (2021) episode of Rick and Morty — the 43rd episode of the series, appearing in Season 5.

“We both had art going on, and he saw my work and bought a drawing on sight,” Lee says. “We stayed in contact, and he gave me his audition drawings from The Simpsons. He wrote a life-changing note telling me how powerful an artist he thought I was. That’s always stuck with me.”

This note gave Lee the inspiration to “keep pushing forward.”

Many of the recurring protagonists Lee paints are unsung heroes or newsworthy figures his uncle and father encouraged him to learn more about. Key examples include Galveston boxing legend Jack Johnson, Houston Astros pitcher J.R. Richard and James Byrd, whose killing by three white men in Jasper, Texas sparked outrage in 1998.

Richard struck out San Francisco Giants Hall of Famer Willie Mays three times in one game. Richard also had a much feared 100 mph fastball. Yet, he eventually ended up homeless after a string of unfortunate events. He was inducted into the Houston Astros Hall of Fame in 2019. Richard appears in several of Lee’s paintings.

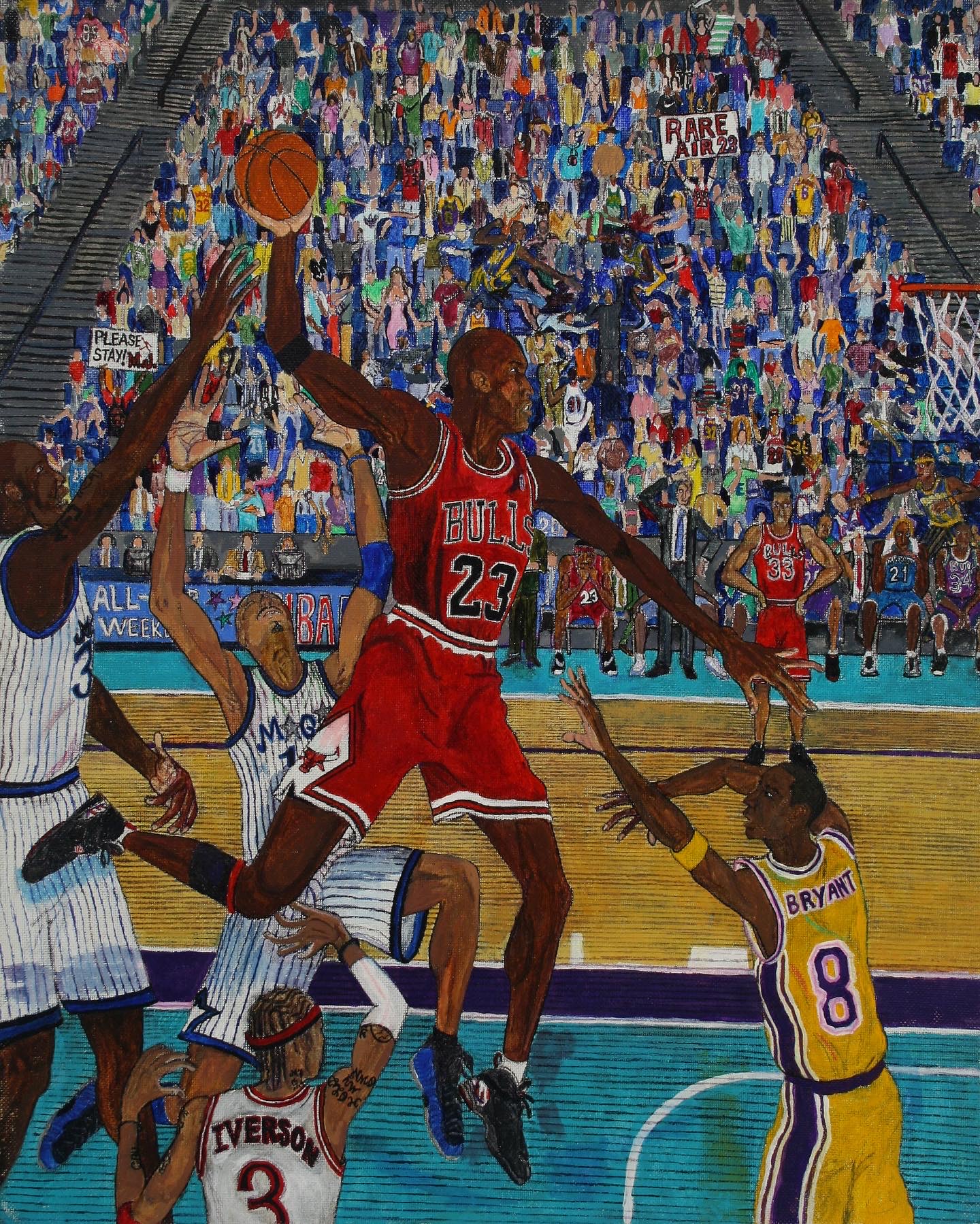

On the sports front, Lee has also referenced Michael Jordan’s illustrious career, the infamous Pacers vs. Pistons brawl and the time Kermit Washington knocked Rudy Tomjanovich out during a Lakers-Rockets game in 1977.

Undoubtedly, the number one painting subject for Lee is the late mythical Houston music legend DJ Screw. He cites Who Next Wit Plex (1995) and Leanin’ on a Switch (1996) as favorite chopped and screwed mixes. Lee likens his painterly style to DJ Screw’s style of mixing and blending records.

“I definitely wanted to be that guy from the North side that knew everything about DJ Screw and what he started, the culture, all the tapes,” Lee says.

Lee describes Screw as a “guru or a spiritual figure. He had that kind of aura when you were around him. On the handful of times I got to be around Screw, or buy the tapes from Screw, it was just like seeing Michael Jordan. He had that glow, that aura. It would be night time, and light would shine from behind him in the doorway.

“He was a real mysterious Yoda or Gandhi-type — a quiet, peaceful guy. He was the most chill person you ever encountered, demeanor-wise.”

An affable and funny recluse who owns a Husky dog, Lee states, rather nonchalantly, that his art-making career began when he was 3-years-old. He later won art trophies for years while attending Will Rogers Elementary School.

Lee says he began making “portraits, busts of Bert and Ernie, Voltron, Spider Man. Making up masks, Halloween masks. Just ninjas, vampires. Everything I thought was cool, I would try to mimic it on paper.”

Artist and curator Mark Flood, one of Lee’s top collectors and creator of the pop-up experimental gallery Mark Flood Resents, champions Lee as someone who reconstructs histories with an innovative approach. He included Lee in a group show entitled “The Future Is Ow” (2016) at Marlborough Chelsea in New York City.

“El Franco Lee II’s paintings mix reality and fantasy in a unique way,” Flood says. “He imagines scenes that might’ve happened. And he adds lots of realistic details to make it seem like a history. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

From Flood’s perspective, Lee’s hybrid reality-fantasy paintings sometimes evolve conceptually from an amorphous, abstract origin.

“In the studio, I’ve seen his unique creative process,” Flood says. “I assumed he painted his paintings from a drawing, or a drawing of a canvas. But I was wrong. He starts out making these abstract paintings that look like colorful fog. In that fog, he finds figures, and brings them to life.

“Maybe that explains why he sometimes arrives at the surprising distortions. Distortions like characters with multiple heads and multiple arms.

“I first heard about El Franco’s paintings when he was at the University of Houston. People told me about him. He had a show there, and I was blown away. I wish I had found out sooner because the prices were going up.”

Curator Christopher Blay says Lee’s smart, Houston-centric approach is unique. The chief curator for HMAAC, Blay first discovered Lee’s work in the Heyd Fontenot-curated “Draftsmen of the Apocalypse” (2014) exhibit at CentralTrak in Dallas. Blay curated Lee’s “Mid-Career Survey” for HMAAC.

Referencing how Lee captures Houston’s music culture, Blay notes: “I think it’s really special because people who have that perspective of growing up next to all of this don’t always create art about it or don’t always write about it.

“To have someone that was there, is an artist, and makes things like that. . . I think it’s pretty amazing.”

Regarding the dark themes of Lee’s paintings, Blay shares: “I think it’s an honest and unflinching reflection of the times we live in. It’s not an aspirational perspective on humanity. We are a species of violence. It has been with us for as long as we’ve been on the planet. It is a dark part of who we are. And I think to El Franco’s credit, he recognizes that kind of embedded violence in human nature.

“His work strongly reflects that in the same way that other artists like Caravaggio and Bosch, people like Francis Bacon, even Picasso, used graphic depictions of violence as a way of exploring the breadth of humanity.”

El Franco Lee II gets sentimental when he remembers Houston art legend Wayne Gilbert, who passed away recently. Gilbert gave Lee his first official gallery show at G Gallery in 2006.

“He inspired me to get a collection of cowboy boots,” Lee says of Gilbert. “He would be wearing these mismatched cowboy boots at the studio visits and when he’d be at art openings. It would be the same brand of boots, just different colors.

“And I was, like, I gotta start buying cowboy boots.”

The “El Franco Lee II: Mid-Career Survey” exhibit is on view through Saturday, September 2 at the Houston Museum of African American Culture, 4807 Caroline St. Learn more here. Lee’s work will also appear in a Houston show entitled “The Devil is a Clown,” opening Sunday, September 24, from 2 pm to 5 pm, at F Magazine, 4225 Gibson Street. That will run through Sunday, November 5.